Lundean’s Nek- Teleriver- Qoboshane- Tele Bridge (RSA/Lesotho border)- Alwynskop- Ha Falatse- Phamong- Bethel- Ketane- Ha Khomo a Bokone-Ha Mojalefa Tsenekeng- Semonkong

Four boys take chase from the last town, meeting us on the road as they shortcut a series of switchbacks that we work desperately to climb. At each turn, they stop and wait without saying a word. They continue the slow run as we pass, keeping aside or behind by only a few feet. Our route is a rough dirt road turned steep 4×4 track, and will soon become not much more than a loose assortment of footpaths and donkey tracks. At the end of the doubletrack-width road, we scout the route ahead. The eldest boy indicates one track versus another. We continue up. Over a thousand feet higher than where they began, the four boys turn back towards home. One is wearing knee high rubber boots. Another is barefoot. They are not winded. Barely in the first grade, these young men are stoic. Children in Lesotho are like men and women, only smaller.

Looking for the route up to the saddle on a goose chase set forth by the pink line on my GPS– one in a series of tracks I casually downloaded from the Dragon Trax website several weeks ago– we push through the boulder field at the end of the road and choose one of many trails into the scrub. Naturally, we follow either the best looking path or the one with the least elevation gain, ascending slowly enough to make me wonder how we will intersect the pass, likely to arrive well below it. Slipping sideways on granular decomposing bedrock, we look upwards. There are a dozen sheep above us along an approximate line on the hillside. Lael thinks there is a better trail. We point the bikes straight up the hill and begin pushing, using the brakes in the manner of an ice axe to hoist ourselves over tufts of brown grass. We drop our bikes along the trail and break for water. Two woman appear from the direction of the last town, carrying small backpacks and large handbags of goods. They walk past without saying anything, barefoot. I am amazed to see them here. If they are surprised by our presence they don’t show it.

The trail continues upwards as a pronounced bench cut by hoof and human, punctuated by steep scrambles through boulders worn into trail. Looking back, I imagine that with some skill, this is mostly rideable. We make only a few pedal strokes up to the saddle.

At the top, a group of five men and women are seated, sharing two large mugs and one big chicken bone. One mug contains a maize drink, lightly sweetened. The other, which they decline to share with us, is an alcoholic maize home-brew. They indicate through charades that it will make our heads crazy. The chicken bone is offered, which I decline. The sweetened maize drink is nice. Reminds me of a drink the Raramuri prepare in the Copper Canyon, Mexico. Two woman in the group ask for “sweets”. We offer a small bag of raisins in trade for the taste of their drink. Lael unveils the raisins as if a consolation for not having chocolates or candy– which we assume they are referring to– but they are delighted nonetheless.

Despite constant exclamations for “sweets!” by the people along the roadside, I haven’t given anything to anyone, at least not since I bought some apples and nik-naks for the young girls that entertained us with a vast repertoire of songs from school. They were adorable, educated, polite– less than five years old, I think– and did not ask for anything. But it was lunch time, and I felt inclined to share something as Lael and I sipped a 1L glass bottle of Stoney. Lael cut up the apples and tore open the bags of puffed maize, instructing them to share with the youngest int he group. They did.

Once the formalities are finalized with the woman holding the chicken bone– pointing to the next village and pointing to the last– we say “Dumalang. Thank you.” and roll over the hill. No one in the group is incredulous that we are on top of the mountain with our bicycles. I am.

On an adjacent hillside is a small round house with a thatch roof, around which dozens of people have gathered near a smoking fire. Something special must be cooking on that fire– an animal, I assume– and the maize beer must be flowing. The group is loud, making an impression of being no less than a proper party, perhaps more. This is Friday night in Lesotho.

Our route continues away from the party, now on a better trail along the hillside which is rideable about half the time, maybe more. We gain some distance on the two barefoot women we met earlier, to lose it at the next short rocky ascent. Coming to another saddle, a group of single-room round houses appear. We arrive just behind the two women, who now laugh loudly. They are tired and happy to be home. I am happy for them, and at least I realize it is amusing that I am here. Several children nearby agree.

We continue away from the village on a wider bench lined with cobbles on either side. The track appears to have been a road, or perhaps was planned as a road. It remains for many kilometers as an easily identifiable corridor of footpaths and donkey tracks, all the way to Semonkong, always with rocks piled alongside. Far from the open roads of the karoo, this is still the Dragon’s Spine route. Lesotho, as it should, lends its own character to the route.

From Barkly East and Wartrail we cross Lundean’s Nek into a fragment of the former Trankei region, between mountains and the border of Lesotho. Transkei was one of several apartheid-era black homelands, or Bantustans as they were later called. We are still in South Africa, but life is different here. There are no white people, and the home life is based upon subsistence farming, not daily toil for basic wages. The result, as I see it in my brief visit, is not a wealthier life, but quite possibly a richer life. Many criticize the black homelands projects for creating regional ghettos based upon race. I agree upon principle. However, the communities seem strong and people seem more open and energetic with us. The Bantustans were designed to become independent states, forcibly separate from the nation of South Africa. If it sounds like a strange and strong-armed social engineering project, it was. While separate from South Africa, none of the Bantustans were ever recognized by any other nation, a purposefully defeating geopolitical purgatory.

Along the Tele River, between the former Transkei and Lesotho.

Villages feature public taps.

There are people everywhere, absolutely everywhere.

While there are several river fords to cross into Lesotho, we continue in South Africa to the official crossing at Tele Bridge.

Ooph. Beware with bottles on the fork that they do not dislodge during rough descents. We’ve made velcro straps to secure the bottles, but this still happened. I went straight over the bars.

Afternoon thunderstorms are becoming more frequent, although not entirely regular. Often, clouds build for hours and hours. We hide inside a store.

Funny guys, tough guys, and nice guys– South Africa is full or characters.

Late in the evening, we make friends at the bottle shop. We are led around by the local English teacher to see the farming project in place on his property. I can tell he’d had a few drinks already. We oblige nonetheless.

We spend time in the bottle shop with a group of young men. This woman owns the shop. Good conversations cannot be taken lightly, and we talk for hours.

We take a tour around town. Many young people out walking in the evening. For the night, we stay inside a fenced property adjacent to the bottle shop.

By morning, we ride into Lesotho.

Free condoms in the toilet. Lesotho has the third highest rate of HIV/AIDS in the world.

Lesotho. South Africa is across the river.

Alwynskop, Lesotho.

We connect to the tar road at Alwynskop for several miles to meet a dirt road toward Phamong.

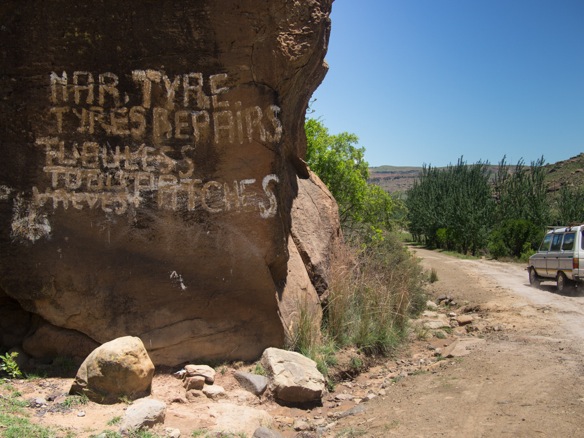

We’ve been told about the condition of the roads in Lesotho. So far, so good. There are many signs indicating projects funded by the USA, EU, and other wealthier nations.

We stop to avoid the sun for some time. Immediately, people move in our direction, toward our bikes, toward us.

This young girl recites a school lesson, “I am a girl. I am five years old. I live in a city. My name is…”.

The group joins for a shoot.

Followed by an impromptu performance of song and dance. The first song is in English, “Early to rise, early to bed…”, while the remaining are in Sesotho. A half hour later I share apples and maize puffs, partly to save these girls from themselves. They are slowly losing steam near the end of the performance.

Day one in Lesotho features incredible roads. But we’re still waiting for the kinds of roads that make this country (in)famous.

Everyone has a voice, and everyone uses it. I’ve never waved so many times in one day.

Another stop. Michael Jackson comes bumping out of this shop. Curious, I enter and buy some maize puffs and a beer. The stereo is operated by the small solar panel outdoors. The rest of the playlist is comprised of African tunes. We’re starved of music, and spend some time in the shade listening.

As Lael boils eggs over a beer can stove on the ground outside, an audience surrounds. Even I recognize how unusual we are, especially Lael. Just as our audience peaks, she often feels the need to fit in her six minute jump roping routine.

The stone-faced group is quickly cajoled into shouts and smiles.

We’re headed to the village of Bethel, where we’ve ben told we can find a Canadian man. No more was told about him, but I am curious. In Phamong, I ask directions to the Canadian. “His name is Mr. Ivan,” I am told.

We find Mr. Ivan and his home, his school, his gardens, and his solar projects. He is a former Peace Corps volunteer who settled in Bethel many years ago, and has been growing his positive influence through education and employment. He’s an eccentric obsessed with solar energy, permaculture, and education. He is exactly what people in this country need. He’s also Ukrainian, via Saskatchewan. It is not until he says “as common as borsch” in conversation that we make the connection. The phrase has now entered my vocabulary.

Our route after Bethel promises to be more adventurous.

We will follow the serpentine line into the mountains, and will stay high on dotted lines until descending into Semonkong.

Climbing from Bethel toward Ketane.

Shops are stocked with maize, maize puffs, vegetable oil, soaps, matches, candles. Cookies, cold drink, and beers are sometimes available. Methylated spirits and paraffin are also common. The official currency of Lesotho are maluti, which are price fixed against the South African rand, which are also accepted everywhere.

Leaving Ketane, toward the end of the road.

These are the boys who steadily chase us uphill.

The end of the road, and the beginning of our adventure into the mountains. The boys return home.

Just a couple of “peak baggers” in Lesotho, coming home from market.

Party house. Friday night in Lesotho!

Every inch of rideable trail is worth the effort. To share the same footpath as thousands of people over many decades is powerful.

The outline of a road guides us beyond the first village.

By morning– in fact, before sunrise– a man calls out loudly in front of our tent. “Morning!”. I hear his voice, unzip the fly, and peer outside with sleepy eyes. He is beaming, wearing a smile. We exchange greetings in English and Sesotho, and I lay back to sleep. He just couldn’t help himself. We made our presence known in the evening to ask for a place to camp. There is plentiful open space here, but people are so curious it is best to introduce yourself. I most villages, it is recommended to ask the chief for permission to camp. Our tent rests between towns for the night.

The idea of a road continues, village to village. There are no vehicles, no corrugated metal, and no outhouses this far out. Eventually, these features return one by one as we near the other end, near Semonkong.

Outhouses and corrugated roofing reappear, indicating our proximity to town.

Finally, we encounter a group of students who have been hired to register voters for the upcoming elections. We make friends with many high school aged youth. They speak English and are more connected to urban styles and global perspectives. Cell phones are ubiquitous.

New styles for the 2015 spring bikepacking season. A photo shoot ensues with both of our bikes and helmets.

At last, the road becomes passable by 4×4., but this last climb has us pushing. From the end of the road near Ketane to the beginning of the road near Semonkong, I estimate that about 50-60% of the route is ridable. Through this section we are on and off the bike frequently, although the connection this route makes is worthwhile.

We join the flow of people to and from town. It is Saturday, and many people are returning from market with 50kg bags of maize meal, large bags of maize puffs, and other necessities and delicacies. It is amazing the things woman can carry on their heads.

Voter registration PSA.

Maletsunyane Falls, the tallest falls in all of Lesotho.

Finally, while a high quality gravel road continues toward town, the local people straight-line over hills to shorten the distance. Our GPS track follows.

Who cares about singletrack when you have six to choose from?

Into Semonkong.

Shopping.

And out of town as fast as we can. The town is deflated after a busy market day. This is our first city in Lesotho, barely more than a few thousand people, and we don’t find much reason to linger. We’re meant to be in the mountains, I realize. The next segment promises similar adventure, as the GPS does not indicate a road for some of the distance. Donkey track, forgotten 4×4 road? Certainly, we’ll find footprints. There are people everywhere.

Really cool guys. Love how good you are at capturing the people you run into- pretty rare for a writing cyclist.

Also, I was wondering how long it was gonna take for one of those bottles to do something bad. A fork leg just seems like the danger zone for carrying stuff off-road

Montana, I recognize and respect the danger zone, especially after riding over the bars. I aim to improve the system and look forward to better cages (perhaps a winged metal cage) and more secure velcro straps. Also, smaller bottles are more secure. These tall 800ml bottles do move a lot on the rough stuff.

Wow, so many great photos, it looks amazing. I’m feeling inspired.

Thanks Sean!

Simply fantastic. I love the 6-track shot, and the chunky nature of the connecting trails. So interesting that such trails can be major commuting routes!

The nature of a “trail” in South Africa is quite different than here in North America. There are few recreational trails, and these are only in urban areas where wealthier folks live. Elsewhere you get are the routes walked by people and their livestock for hundreds and sometimes thousands of years. In the KwaZulu-Natal we could travel for upwards of a hundred miles without passing through a village with a single vehicle. Everybody walks, and these footpaths are everywhere. In the mountains sheep make the trails, and sheep tend to travel directly across precipitous and unnerving slopes. I admit it made me wistful for all of the hard work and planning that goes into trail building in the U.S. It’s a different experience, even compared to more primitive trails that I’ve hiked in Alaska and Montana.

Great photos!

Jill, You’re assessment is mostly on par with my own. Much of the rough stuff riding that people speak of in this country happens during scheduled events such as the Cape Epic or the 2Sea series of races in the east. These all take place on private land on scheduled tracks on a given date. I think these inform MTB in ZA more than anything, officially. However, for the adventurous types there are some regions where more natural trails can be found, with some necessary hike-a-bike. I’m not sure how many people are actually doing this kind of riding, outside of the FC and the usual outliers. In fact, I haven’t seen a single mountain biker in two months!

You say that walking trails go for miles through the mountains in KZN, although I think more accurately it is the former Transkei (mostly in KZN and Eastern Cape) which lacks massive farms and fencelines, and enable miles of walking trails. Blacks were denied the right to private property in 1913 by the Natives Land Act (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natives_Land_Act,_1913), which reserved lands for communal use, a precursor to Apartheid and the Bantustan projects. For better or worse, the result is a more natural distribution of people on the land, as in Lesotho.

Like superhighways for donkeys, people, 50kg bags of milled maize, and giant bags of Cheetos (name brand Nik-Naks, although the off-brands are ubiquitous in Lesotho).

N: Sorry to hear those kids of Lesotho are still chasing after cyclists demanding sweets. I had the same experience in February of 2009. I even had a few try to grab water bottles off my bike and dangling socks that I had drying on the back of my bike. At least you’re not encouraging them by giving in, as some must to keep them at it. I was also marooned twice by overflowing rivers and enjoyed great hospitality by locals while waiting for the water to recede.

Great photos and commentary as usual.

Regards, George

George, The children are mostly innocuous, if bothersome. I’m holding my tongue for now as I know we’ll see more of this in the near future as we ride north. However, at the end of every day, Lael and I would wonder how the three words that everyone knows in the country are “Give me sweets!”. Either teachers or parents are responsible, especially as these are the ONLY three English words many children know. A boulder did come tumbling down towards me from a mountaintop, several boys cheering from above. This was near the Khatse Dam, which seems to evoke genuine spite from the people, especially as South Africans come in droves to visit this man-made wonder.

I wonder who is to blame for the concept of giving sweets? Sugar-coated crosses of Jesuit missionaries, white guilt tourists from RSA/UK/USA, or just the usual visitors wanting to make some kids smile for photos. It is disappointing to me as it gets in the way of more meaningful conversation. I made my best effort to turn it around by asking names, ages, about school, math questions, etc. Most children were willing to forget about sweets to talk. Those that didn’t, get ignored.

N: Based on my experience over the years in other parts of the world, kids become conditioned by well-meaning, but misguided, tourists and travelers who wish to dispense small gifts to the cute and needy, thinking they are doing some good. The kids come to recognize Westerners as gift-givers and, as we have both experienced, pursue them relentlessly, sometimes for miles. In Morocco kids would approach asking for “un pluma,” French for a pen, or “un dharma,” their unit of currency, as they had on occasion been bequeathed. Men would run across fields at the sight of me shouting “un cigarette.” In Nepal children came trotting to me happy for whatever I might be giving.

Back in the days when the yen was so strong and Japanese tourists were a frequent site in Chicago, if they had been known to pass out cameras, it would have been hard to resist charging after them. So I do not blame the askers, it is the givers who have created this pestilence.

It was an entirely different story in Laos. I biked through shortly after the country had been opened to non-package tour travelers and the children had yet to be corrupted. All they wanted was a wave in return for their wave. I doubt though that it is still that way. That was fifteen years ago. They no doubt are now like those in Lesotho, Morocco and Nepal, sorry to say, and have become wanters rather than welcomers. I saw the same transformation in Guatamala from the early days of low budget travelers ,who were on the road for months, to the invasion of the moneyed-set jetting in for a week, flaunting their wealth and wanting to be do-gooders. They may think they are being beneficent giving something useful such as a pen or pencil, but it corrupts the kids the same as giving a Bon-Bon or a balloon. The best they can do is as you do, simply being interested and friendly.