Prince Albert- Willowmore- Steytlerville- Jansenville- Graaff-Reinet- Nieu Bethesda- Middelburg- Steynsburg- Burgersdorp- Jamestown- Roussow- Barkley East- Wartrail- Tele River

There are small towns and expansive farms with teams of farmworkers in blue cotton coveralls slowly working under the sun in full-brimmed caps. There are afternoon winds and windless starry midnights. Kudu sausage and lamb chops on our plates indicate the presence of wild game and managed stock, especially Merino sheep and Angora goats. Twice, antelope race alongside the road excited by my 18mph presence, afraid or unable to cross the barbed wire fence. Once, I reach past 35mph with the assistance of a powerful tailwind, gaining on the full-tilt sprint of the animal. At last, side by side, it cuts right toward the fence and jumps. Tired or distracted or unable to jump high enough, it somersaults into barbed wire in a flurry of fur. It watches as I disappear down the road. Both our hearts are racing.

This is the karoo. Our first attempt to leave Prince Albert, situated on the north side of Swartberg Pass, is foiled by strong headwinds on washboarded sandy roads. We turn back to spend another day in town. There, while sitting by the curb drinking from my water bottle, a man pulls up in a white bokkie. He invites us to join him for drinks with a few friends, which necessarily means multiple rounds of brandy and coke, plates of meat, and hot chips. He invites us to stay at his house. The next day, we tour his stonefruit farms where he grows peaches, apricots, plums, and nectarines in a series of drainages where the waters of the Swartberg Mountains meet the sun of the karoo. Any further into the karoo and he’d be the owner of a dusty sheep farm, but here, he manages a vast oasis which employs as many as 184 people during harvest. In the evening, we prepare a braai. On the second day, after wind and rain have subsided, we head east. For the next two weeks from the Swartberg Mountains to the Drakensburg Mountains and the border of Lesotho, we’ll not escape the embrace of similarly generous farmers, wide open gravel roads, and endless sunshine. In consecutive nights, we are treated to farm-fresh lamb, indoor accommodations, and company. If you ask for water in these parts, you’re likely to get a whole lot more.

The riding is as I often say, “Divide-style riding”, named for the Great Divide Route. The gravel roads are maintained to a high standard, towns come once or twice day; food, water, and camping are fairly straightforward, especially if keeping to public routes. Our fortune continues all the way from Cape Town as tailwinds shuttle us to the north and east. As our path curves through the karoo, the winds shift to our backs. I don’t know what has brought us such good fortune, but I am grateful. With few exceptions, we’ve enjoyed weeks of tailwinds. I am not sure why both the Freedom Challenge and Dragon’s Spine routes are scheduled in the opposite direction, although they can be toured in any direction.

On our first day out of Prince Albert we continue on the Freedom Trail (more accurately, the Freedom Challenge Race route) to Willowmore. There, we will decide if we continue on the Freedom Trail or the Dragon’s Spine route (GPS tracks; Riding the Dragon’s Spine guidebook), which we have just discovered. One requires some advance planning, communication with the race organizer, payment for lodging or traversing permits, and eventual portages including a notable 4×4 track east of the Baviaanskloof, which would be our next stage. Further, the race organizer is suspicious of how we will supply ourselves with food, and if we will be able to heft our bikes over 3m tall game fences. He and I disagree about the term self-supported. The Dragon’s Spine entices us with a rideable route on public thoroughfares, eventually deviating into Lesotho and continuing all the way north to the border of Zimbabwe. The route also passes near Swaziland, enabling a quick trip into that country’s mountainous western half. The decision is easy. We begin working towards becoming Dragonmasters out of Willowmore.

Separated by fifty miles of open country, karoo towns melt together, yet slowly change from the whitewashed touristic strip of Prince Albert in the west to the mostly black communities of Barkly East, near Lesotho. Despite this major trend, one town may be manicured and orderly while another is disheveled and drunk by noon, for lack of work and purpose. I find it difficult to make conversation with poor blacks in this country, at least those that wear blue coveralls to work, which is the universal laborers uniform in South Africa. Most blacks live in sprawling townships of ramshackle government housing outside of town, vestiges of official apartheid programs. Footworn dirt tracks lead between town centers and black townships, and mostly unpaved streets connect rows and rows of houses, which may or may not have electricity. Many homes feature passive solar water heaters on the roof.

It is only outside the bottle shops and tuck shops that we share a few words, as passersby marvel and squeeze our tires. While resting in the shade eating a papaya and maas, a local cultured dairy preferred by blacks, we receive friendly and curious looks. I imagine their wonder, “why are those sunburnt white people sitting on the ground to eat?” Some people must realize we are tourists; schoolchildren and groups of woman carrying goods on their head shyly turn away to laugh amongst themselves. A man is sitting on the sidewalk twenty yards away, in front of a small panel of particleboard topped with shoeboxes of generic Nik-Naks– popular maize cheese puffs– and some barely past ripe apples. We look towards one another, each as curious as the other. We smile and nod, as if part of a secret club of humans than still knows sitting on the ground in the shade is a good use of time. I think so.

I haven’t heard the word racism in South Africa, yet I can’t get away from it in American media, even from afar. We do share healthy conversations with white farmers in the evening about the direction of the country, the degradation of the schools since “they” took power of the country, the ANC party, and the rising cost of labor. We are guests in their homes and in their countries. And I mean what I’ve said before, we meet some of the loveliest people in the karoo. These people are living honest Christian lives. Its just that they grew up in a system of legislated segregation, with hundreds of years of black labor to thank for their farms, their railroads, skyscrapers, and their wealth. And as the owner of a potato chip factory likely complains about the seemingly inconsequential rising cost of salt, white farmers challenge the rising minimum wages in this country. Different sectors of the economy maintain unique minimum wages, including the hospitality industry (home workers, mostly, not hoteliers) and farmworkers, the two labor groups we meet. In an article dated from 2013, the minimum wage for farmworkers was reported to have increased from R69 a day to R105, a 52% increase. Yet, that’s an increase from about $6 dollars to $10 a day at current exchange rates. A can of Coca-Cola costs about $0.60, a full plate of Take-Aways is usually $2-$2.50, and while plenty of bottled beer and Cokes are consumed in this country most laborers and their families subsist on fortified maize meal. As above average inflation plagues the South African currency, wages diminish in actual value while farmers who export their products gain from the devalued currency. Exotic mohair for export? Peaches and apricots off the tree while the southern USA and Turkey are frozen for the winter? South African farms are far less mechanized than in America, where farming on a massive scale is the only way to compete. The farm industry seems healthy, but there are sighs late at night. “It’s hard.”

For us, there is still more to unravel. Indians were also disenfranchised during apartheid, although less so than blacks. “Coloureds”, an official class of mixed race persons also including Malays and others, fit somewhere in between. Asians from certain nations, usually trade partners of South Africa, were given exception as “honorary whites”. I’m can’t seem to find any honor in the situation. And while the task of classifying the population was a continual challenge, it stands that the most important statistic is that the elite class of whites make up less than 9% of the country’s population, descendants of Dutch, English, French, Scottish, and Germans, mostly. But they don’t control the government anymore, at least not since the first universal democratic elections in 1994.

The country is not unsafe. Gruesome crimes are described, such as a well-reported series of farm attacks across the country, most likely crimes of desperation. We’re constantly reminded and warned of theft. But the streets of small cities and towns do not bear any aggression. People are nice. Markets are bustling. The population is young and growing. A peaceful disharmony exists, although periods of struggle are likely to shape the future.

I didn’t know anything about South Africa two months ago.

Out of Prince Albert. Into the wind.

Jaco rescues us from the roadside, settles us at his home, and feeds us heartily. He has made several journeys to Namibia by motorbike and recalls the hospitality he received while there. Clean clothing was a highlight. He plans a motorbike trip from Cape Town to Cairo in the future, if he can ever get away from the trees. In addition to fruits, he also grows onions for seed, a common crop in the mountains before the Great Karoo.

His fruit sorting facility is nothing like I expected. The computerized system inspects and sorts fruits on a massive scale. Laborers harvest the fruit.

Back on the Freedom Trail, toward Willowmore. The thorny acacia is omnipresent in this part of the karoo, a subregion called the thornveld. Veld is Afrikaans, literally meaning field.

Not much out here other than windmills and stock tanks, miles of barbed wire, and the occasional farmhouse. When someone says “pass a few farmhouses”,that can be ten miles or more.

We stop for some water at a farmhouse. Incidentally, this is a mid-day stop during the Freedom Challenge race. We ask how frequently they see riders outside of the race. Very few, it seems.

Many farmhouses date back a hundred years or more, and are composed of several accretions over the years. You’ll find some unusual floor plans in these homes.

Angora goats, whose hair is called mohair, characterized by long, silky fibers. Angora fibers come from an Angora rabbit.

As we request water at dusk, we are invited indoors. Invited to an impromptu meal, prepared by a farmer whose wife is away for the evening. He keeps goats and sheep, some for their fibers and others for meat. Two ostriches are what remain of a once profitable ostrich farm..

He is a gracious host willing to share his stories and impressions of the world. We’re fascinated to learn what people think of our country, although I didn’t know anything about this place until recently. If he looks a little out of place in the kitchen, it may be the case. He apologetically assembles a series of sandwiches and hurriedly thaws some meat from the deep freeze. But of all the lamb we taste in the karoo, this may have been the best. Perhaps it is the instruction to simply take it from the fire with bare hands that makes it taste to good.

Kudu boerwors and lamb.

All sheep farmers are former rugby players. All karoo farmers love to eat meat. South African men take great pride in their braai, both the technique and the equipment. His braai is homemade from an oil drum.

The next morning we detour towards a possible connection with some hot springs which Johan has recommended. Still early in the morning, we opt to continue riding. However, these unimproved springs are located with a waypoint on the Tracks4Africa GPS basemaps. From the north, you can follow the rail line from Vondeling Station between the mountains.

Rains re-awaken the desert.

A few towns offer a limited touristic infrastructure, which diminishes as we travel east away from the reach of Capetonians. Eventually, small towns feature a single aging hotel at the center of town.

Willowmore.

Outside of town, the black townships sprawl into the veld. Each township appears like an upscale suburban neighborhood on my GPS, but I soon learn the pattern of the land. White people live on farms in the country or in the small grid of old homes in town. Blacks live in farm housing, or in sub-urban townships as much as several kilometers from town. The quality and vintage of the housing varies.

Along the Groot River for the evening.

Some farm housing, more substantial and scenic than most. No electricity, no running water, and only salvaged wood to heat the home and cook.

Again, at dusk, we inquire about water and a place to camp. We are offered a place on the lawn. By morning, we’re called to a hearty farmer’s breakfast of eggs, sausage, and toast with coffee. Homemade marmalade is a highlight.

This is our turn, of course.

Steytlerville.

Jansenville. Ripping tailwinds put us over 100 miles on this day.

Again, with the plea for water, we are offered a place to sleep. Rather, I try to insist we sleep outside but it seems foolish in light of the offer. A guest cottage down the road is our home for the night. As we step out the door, Sydney and his wife Gay hand us two freezer bags of meat. One is kudu sausage, or boerwors (farmer’s sausage), and the other are lamb chops. We’re tired, but we start a fire outdoors to cook the meat. There is only one way to prepare meat like this. It would have been a shame to waste it in the pan.

In the morning we are again called to breakfast, and asked to assist with a special project. A ewe is suffering from severe mastitis and cannot feed her young. Lael sternly assists in the delivery of a formula.

And before we go, a meat snack for the road– homemade kudu biltong. This lean cured meat is like jerky, but usually requires the aid of a knife to portion it into manageable bits.

These days, we’re carrying as much as 4-5 liters of water each. That full quantity is only essential if we expect to camp overnight. The system of bottle cages on the fork was first devised for long stretches of the Freedom Trail, although established water sources are more plentiful on the Dragon’s Spine route. Each side of the fork holds 1.6L of water in two cages, tightly taped to the fork with about a half a roll of electrical tape. Other tape works just as well, but the trick is to get it tight. With two bottles playing precariously near to the front wheel, we fashioned some velcro straps for security.

Note, we are carrying a pack of water treatment tablets purchased in Cape Town in case we require them, but are relying upon taps in town or on farms, and occasionally at stock tanks. If we camp near a water source we will prepare hot food or drink from the source, bringing the water to a boil.

Graaff-Reinet.

At the Spar supermarket, Braaipap is marketed toward a white Afrikaner audience. Everyone eats maize in South Africa, cooked into pap, usually the consistency of thick grits or polenta. Poor families rely upon it as a staple, usually purchased in 25 or 50kg bags. Most common brands of maize are fortified. About 11 or 11.5 South African rand to the dollar this week, so even these 5lb bags of premium maize are less than $2.

Stopped to camp by the roadside. Lael is still jumping twice a day.

Erasmuskloof Pass, just a little notch in the many small mountains that dot the karoo.

Thankfully, all the gates on these public routes swing open.

Nieu Bethesda, a quaint little town in the karoo that white people like to visit. Situated at 4500ft in a small mountain valley, it really is a beautiful setting. Read more about it on the Revelate Blog.

Several kitsch-chic cafes serve the touristic community. A local brewery offers these fine unfiltered ales.

Dirt Busters by Deon Meyer is a great resource for off-pavement routes across the country. Meyer is an Afrikaans novelist famed for thrillers.

Signs in miles, before converting to metric.

Droewors, Afrikaans for dry sausage.

Camped inside a game reserve, we hear antelope and zebra throughout the night.

Here, our GPS track chooses a less travelled doubletrack. Admittedly, I don’t have the complete guidebook of the route. I glanced at a few pages in Prince Albert before I was certain that we’d be riding the route. There are some inaccuracies and missing sections in the GPS files offered on the Dragon Trax website, not unusual for a new resource like this. I’ll see if I can offer some improved tracks.

Just to see how one might singlehandedly cross a 3m game fence with a loaded bike, I pass the first 2m fence in front and hoist my bike to the top of the taller fence.

Let it down slow.

Middelburg. The owner at the dainty Afrikaans coffee shop (tea room/craft center/jam cellar) asks if we have a way to cook some sausage. Sure! I expect she will return with a small freezer-pack of local boerwors. She returns with a large plastic bag of fresh, never frozen local kudu sausage. At least six or eight pounds in total, maybe ten. I make room in my seatpack, which I just packed with two days of food.

Seeing as the sausage must be cooked immediately, we set about on a mission. A gravel pit, salvaged fencing and barbed wire, and scrapwood from the veld serve to make an impromptu braai for our meat. Under clear skies and with a chilled bottle of sauvignon blanc from town, we sit and slowly cook the wors.

Such high-quality lean meat has us soaring for days. We both enjoy meat, but this was some superfood. Biltong is second best.

Steynsburg.

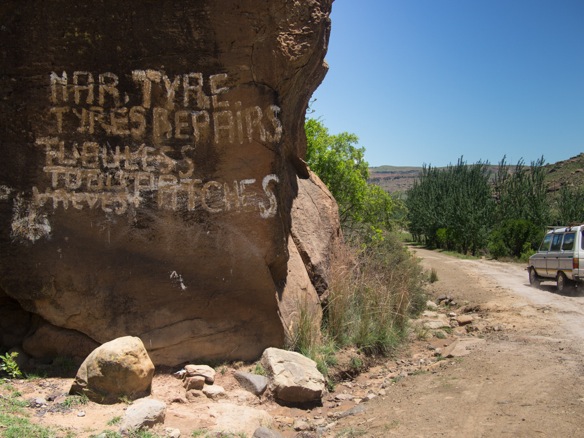

I’ve stopped many times to offer air to riders whose tires are gradually and continually losing air. This bike has been converted to a singlespeed. The frame is broken at the top of the seat tube, has been welded, and is broken again. The front wheel is from an English three speed, 26 x 1 3/8″, and uses a Dunlop valve. The rear Schrader valve was no problem for my Lezyne pump though.

There is surprisingly little washboard on these roads. When we tell farmers that the roads are very nice in their country, both the paved and unpaved roads, they are astounded. Somehow, the world imagines everything is perfect in America.

Burgersdorp.

I’m pretty much fluent in Afrikaans, as long as it relates to coffee, tea, sugar, cookies, and milk. One-stop shopping in aisle two.

Another black township on the edge of town, this one is called Mzanomhle. These townships typically include many of their own shops, schools and other services. Rugby and cricket are popular sports for white youth. Football, sometimes also called soccer, is a black sport.

This is approximately what I see on my GPS when entering town. I know the classic grid in white near the intersection of the main yellow roads will be the town with the main shops, owned by white Afrikaners, Chinese, and Indians, mostly. The complex of red communities are the black townships. Oh, and the red lines are dirt streets. The white ones are paved.

Commuting to work. This rider caught up with me on a short climb, although my excuse is that we had just started pedaling for the day. I need some time to warm up.

Jamestown.

You can’t go wrong in this freezer.

Schools are an important part of life for children here, and during the day groups of children in uniform populate the town during a midday break. These boys enjoy the afternoon after a half-day of school on a Friday. After a substantial English exam in the form of a lengthy conversation in which I asked everything I’d been dying to know about lives in the township, I share a bag of cheese flavored corn puffs with them. The eldest boy on the left is the most outgoing– in English at least. His mother works as a cook at the school and his father drives an ambulance. Their favorite meal at school is chicken and pap. There are eleven official languages in South Africa, including 9 native languages besides English and Afrikaans. English is the official language of government and business, but many whites grow up speaking Afrikaans, especially on farms. However, everyone speaks some English, and there are truly English families, some of which speak the language, and others who also trace their ancestry to the Isles. Some of the other languages include Xhosa, Sotho, and Zulu.

There are schools that teach primarily in English, Afrikaans, and any of the other nine languages. All teach some English, and many still teach some Afrikaans. However, attending a proper English school is a huge advantage for these young boys.

Not far down the road, perhaps an hour or two, we are stopped by a passing truck to come fill our waters at their farmhouse down the way. We stop, we talk. We play with the kids. Now, we are asked to stay for dinner and to stay the night In that case, I jump in the small above ground pool with the kids.

They show us around the farm, home to hundreds of merino sheep. They will be sheared several times, but eventually they are sold to slaughter.

She is as charming as she looks, and has taken a liking to speaking English although her family mostly speaks Afrikaans at home. Who says TV is a waste of time? Despite her indoor education (even before school age) she is most at home outdoors running barefoot through pens full of sheep shit. Her older brother will soon move away to boarding school for the semester. Most farm children move away for school, as young as 5 or 6 years old. They grow up quickly.

Their father Casper is the head of the provincial wool growers association. In addition to facilitating the industry across a vast area, he is also involved with a program to connect upstart black farmers with the skills and expertise they may need to achieve independent success– a refreshing perspective. Livestock theft is common, especially at night. He says it happens frequently on a full moon. This is one of few farm families that did not have a servant in the house during the day. At less than a dollar an hour, it now makes some sense to me how people can afford this.

Dordrecht.

I’m still trying to unravel the marketing mystery of coffee and chicory in this country. All share almost the exact same packaging and claims of being “Rich and Strong”. They’re are all cheap and tolerable, easy on the stomach, and virtually caffeine-free. They brew a dark pot best enhanced with a spoonful of sugar. We’ve grown to like it even though real coffee is available at the fancy supermarkets. Rooisbos tea is also a favorite midday drink as we pass time in the noon hour in the shade.

There is either an Anglican or a Dutch Reformed Church in each town, or both.

Roussow, an exclusively black community without any historic infrastructure, no grid, no old church. This village reminds us of some reservations in America.

Again, we replay the request for water and receive a room for the night. Twenty four year old Vossie is living by himself in a five-bedroom house, managing part of a sheep farm with over 8000 sheep. His parents and brother live several kilometers down the road. Hard rain falls through the night and all through the next day. We spend the day drinking coffee, napping, and watching bad movies with Vossie on TV. He is the sixth farmer we have stayed with, the fifth to prepare lamb for us, and the sixth to also be a rugby player. One of the few white people we have met near our age, we is refreshingly aware of life in America. Again, a little TV never hurt, although he was concerned we might all be gun-crazed hoarders preparing for the apocalypse. I think the Discovery Channel is to blame. Lots of American TV is exported to South Africa.

His home is tucked up into the hillside, near 6000ft. From Prince Albert we have slowly ascended from about 2000ft. From here, we remain above 5000ft all the way through Lesotho, the Mountain Kingdom. We’re getting close.

Shuttling sheep along the paved road with flaggers.

Barkly East.

Take a look at the local slaghuis, the butcher shop, for some delightful dried meats. We buy half a kilo of biltong and half a kilo of droewors to pack into Lesotho.

The Dewey Decimal System, in Afrikaans.

Some Xhosa books.

Natural products and tinctures on the shelves of the local market.

There is a small stifling culture of inns, teas rooms, and coffee shops operated by white Afrikaner woman. I suspect much of this will disappear in the next generation.

This is more or less how Lael sees things.

Railroad switchbacks. Took me awhile to understand this.

Hansa Pilsener is a popular SABMiller product, a fraction of the company’s global beverage dominance. The original South African Breweries (SAB) originated in 1895.

The Drakensburg Mountains are surfacing.

Protein loading.

What’s that, a bag of meat?

In our last night in the country before crossing into Lesotho, we meet another sheep farmer. Vossie mentioned a friend who had a farm near Wartrail on the right. I assumed his instructions were lacking detail and ignore them. By chance, when we ask for water, he’ve hit the mark. Another guest cottage for the night. Just ask for water.

Off to Lesotho!

Just a sliver of South Africa left, through the Transkei region along the border before crossing at Tele Bridge. Should be all mountains and crumbling dirt roads for the next week or more!